Objectives: The practice of regional anesthesia techniques (thoracic, epi dural, paravertebral) in pediatric cardiac surgery enhances perioperative outcomes such as improved perioperative analgesia, decreased stress response, early extubation, and shortened hospital stay. However, these blocks can be technically challenging and can be associated with unacceptable failure rate and complications in infants. For these reasons, regional anes the sia is sometimes avoided in pediatric cardiac surgery. We describe the simple and effective serratus plane block for thoracotomy analgesia in 2 neonates and a child.

Case Report: We present 3 pediatric patients, each of whom was having coarctation repair and received an ultrasound-guided serratus plane block for thoracotomy analgesia. The patients were 3 days, 14 days, and 4 years old, weighing from 1.9 to 16 kg. The serratus plane block was performed prior to surgical incision. The block was technically simple compared with thoracic epidural or paravertebral block. All patients were extubated immediately after completion of surgery. Apart from the induction dose of fentanyl (2 μg/kg), no further opioids were required intraoperatively. Postoperative opioid requirements as well as duration of intensive care and hospital stay were lower than recent averages (for the same demographicand procedure) in our hospital.

Conclusions: We proposethat the serratus planeblock is a simple procedure that provides good perioperative analgesia for infant thoracotomy, potentially facilitating early extubation and a shorter hospital stay.

(Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018;43: 641–643)

Caregiver written consent was obtained for publication of these case reports.

Case 1

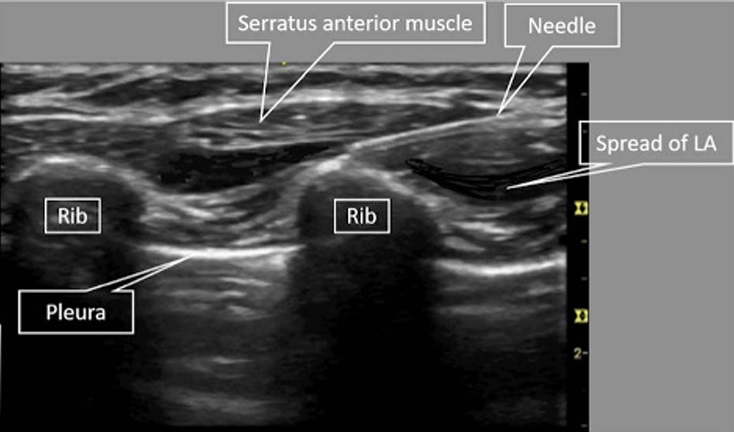

A 14-day-old boy weighing 3.60 kg wasscheduled for repair of coarctation of the aorta. In the operating room, he was anesthetized and then positioned in right lateral decubitus position with the left arm flexed and adducted across the chest away from the surgical field. The intended site of incision, extending from the midaxillary to the posterior axillary line at the level of the sixthrib, was marked by the surgeons. Ultrasound-guided serratus plane block was performed at this level (Fig. 1). Under aseptic conditions, a linear ultrasound probe (L25xp, 13–6 MHz; Fujifilm SonoSite,

Bothell, Washington) was positioned in an oblique plane over the skin (so as to view the ribs in cross section) in the midaxillary line to visualize the sixth rib deep to the serratus anterior muscle. A 50-mm echogenic needle (Sonoplex STIM, 22 gauge 50 mm;

Pajunk, Geisingen, Germany) was inserted in plane, using the technique (Fig. 2). Hydrodissection with 0.25 mL of the local an esthetic was performed to identify separation of the serratus muscle from the rib and intercostal muscles (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AAP/A247, video showing spread of local anesthetic). A total of 3.5 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine was injected in this plane, and extensive spread in this plane was visualized ultra sonographically. Surgical incision occurred 15 minutes after performing the block, and the duration of surgery was 1.5 hours. Vital signs remained stable after skin in

cision and throughout the surgical procedure. The anesthesiologist was ready to administer intravenous opioids, but absence of any response to surgical stimulation suggested this was unnecessary, and none were administered during or immediately after surgery. The trachea was extubated at the end of surgery, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where hestayed overnight before transfer to the cardiac ward the following day. He was discharged home on day 2 after surgery. He had received a single dose of intravenous morphine 50 μg/kg during his ICU stay and 2 more doses of oral morphine (200 μg/kg) during the entire postoperative period. He had also received regular acetaminophen 15 mg/kg orally every 6 hours.

Case 2

A4-year-old girl weighing 16 kg was scheduled for repair of coarctation of aorta. Anesthesia was induced intravenously (including fentanyl 2 μg/kg). An ultrasound-guided serratus plane block was performed at the midaxillary line at the level of the surgical incision after induction of anesthesia. A total of 16 mL of 0.25% bupivacainewith 1:200,000 epinephrine was injected deep to the serratus muscle over the fifth rib using the technique de scribed previously. No objective markers of pain were witnessed; thus, no further intraoperative opioids were administered. The trachea was extubated after completion of surgery, and the child was transferred to the ICU where she stayed for 1 day before being discharged to the cardiac ward. She was discharged home 1 day later. Posto peratively, she received regular acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 6 hours), ketorolac (0.5 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours), and a total of 3 doses of or almorphine (200 μg/kg) during her stay in hospital.

Case 3

A3-day-old neonate weighing 1.93 kg was scheduled for repair of coarctation of aorta. Apart from coarctation of aorta, the child also had ambiguous genitalia, which was underinvestigation by the endocrinology service. This child received an ultrasound

guided serratus block (1.5 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine with epi nephrine) at the lateral thoracic wall at the site of surgical incisionprior to incision. Apart from the initial intubating dose of fentanyl (2 μg/kg), no further intraoperative opioids were administered.

The child was extubated after surgery in the operating room. The patient received 1 injection of intravenous morphine (50 μg/kg) in the ICU where he stayed a single day. He was discharged to the ward the following day, where he received 2 more doses of

200 μg/kg of oral morphine. Because of associated endocrine pathology under investigation, the patient remained admitted in the endocrinology ward of our hospital for 4 further days.

We report the use of the serratus plane block to provide peri operative analgesia in 3 pediatric patients undergoing coarctationrepair. Tracheal extubation was possible immediately after surgery in all these patients. Time to extubation was shorter than reported previously for children aged 1 day to 6 years undergoing coarctation repair without regional anesthesia (mean, 7 hours).5 In addition, we observed shortened ICU and hospital stay compared with the average for this surgery (mean, 2 and 4 days, respectively).5 We recognize that with rapidly evolving postsurgical care and enhancedrecoveryquoted recovery times can beshortened by multiple contributing factors. In our hospital, the mean ICU length of stay (over the last 2 years) is 2 days, and hospital length of stay

FIGURE 1. Patient position for the block.

FIGURE 2. Ultrasound image of guided serratus plane block.

is 5.5 days (for similar patient and operation), both of which are longer than what we observedin this caseseries, although we are cautious not to overstretch conclusions drawn from these 3 cases.

In ourinstitution, postoperative pain in this age group is evaluated using a FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) score,6 where a child with a score of more than 3 would be given a dose of intravenous morphine and started on morphine infusion if bolus doses failed to achieve adequate analgesia. In our 3 patients, FLACC scores were consistently less than 2, which we took as an objective indicator of effective perioperative analgesia conferred by the serratus block. The anesthesiologist performing the serratus block was not the attending cardiac anesthesiologist for the case and had no further involvement in the case intraoperatively or postoperatively. Although the use of the block was handed over (ie, there was no blinding), it was emphasized that pain assess ments and consequent opioid administration should be conducted as for anyother patient. We areconfident that opioidswere not being withheld because of the use of a regional anesthetic technique. Regional anesthesia such as thoracic epidural and paravertebral block not only provides opioid-sparing analgesia, but also has benefits with respect to ventilation7 and potentially decreases post thoracotomy syndrome.8 Although it has been shown to improve perioperative outcomes, the procedural challenges in neonates and small children, along with potential complications, of ten outweigh the clinical benefits.9 The serratus plane block was initially described by Blanco et al4 as an analgesic technique for adults undergoing breast surgery, but it has also been used successfully to provide analgesia for rib fractures and thoracotomy.10,11 It is considered technically easy and potentially safer as the target is a fascial plane and not a particular nerve or the spinal cord.4 The plane of the serratus block is superficial to that for intercostal nerve block and iscomparatively less vascular. Accordingly, the serratus plane block may be associated with a lower incidence of block-associated pneumo thorax and local anesthetic systemic toxicity compared with intercostal nerve block.

The serratus plane block provided good analgesia for thoracotomy in pediatric patients. It may provide an alternative analgesic technique when thoracic paravertebral or epidural blocks are contraindicated. Future studies will clarify the place of serratus plane block for pediatric thoracotomy and begin to establish its safety profile.

1. Peterson K, DeCampli W, Pike N, Robbins R, Reitz B. A report of two

hundred twenty cases of regional anesthesia in pediatric cardiac surgery.

Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1014–1019.

©2018 American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

Copyright © 2018 American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine • Volume 43, Number 6, August 2018

Serratus Block for Coarctation of Aorta

2. Wolf AR, Eyres RL, Laussen PC, et al. Effect of extradural analgesia

on stress responses to abdominal surgery in infants. Br J Anaesth.

1993;70:654–660.

3. Bastero P, DiNardo J, Pratap J, Schwartz J, Sivarajan VB. Early

perioperative management after pediatric cardiac surgery: review at

PCICS 2014. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2015;6:565–574.

4. Blanco R, Parras T, McDonnell JG, Prats-Galino A. Serratus plane block:

a novel ultrasound-guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anaesthesia.

2013;68:1107–1113.

5. Tabbutt S, Nicolson SC, Dominguez TE, et al. Perioperative course

in 118 infants and children undergoing coarctation repair via a

thoracotomy: a prospective, multicenter experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc

Surg. 2008:136:1229–1236.

6. Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC:

a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children.

Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23:293–297.

7. Groeben H. Epidural anesthesia and pulmonary function. JAnesth.

2006;20:290–299.

8. Karmakar MK, Booker PD, Franks R, Pozzi M. Continuous

extrapleural paravertebral infusion of bupivacaine for

post-thoracotomy analgesia in young infants. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:

811–815.

9. Rosen DA, Hawkinberry DW 2nd, Rosen KR, Gustafson RA,

Hogg JP, Broadman LM. An epidural hematoma in an

adolescent patient after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;

98:966–969.

10. Fujiwara S, Komasawa N, Minami T. Pectral nerve blocks and

serratus-intercostal plane block for intractable postthoracotomy syndrome.

JClinAnesth. 2015;27:275–276.

11. Kunhabdulla NP, Agarwal A, Gaur A, Gautam SK, Gupta R, Agarwal A.

Serratus anterior plane block for multiple rib fractures. Pain Physician.

2014;17:E553–E555.