Background and Objectives: Truncal blocks have a place within multimodal analgesia techniques in abdominal surgery. The quadratus lumborum block is a new abdominal truncal block used for somatic anal gesia of both the upper and lower abdomen. In this prospective, double blind, randomized study, we aimed to compare quadratus lumborum block and transversus abdominis plane block in pediatric patients undergoing lower abdominal surgery.

Methods: Fifty-three children undergoing unilateral inguinal hernia repair or orchiopexy surgery were randomized into 2 groups: transversus abdominis plane block and quadratus lumborum block. All blocks were performed under general anesthesia before surgery. Pain levels were assessed using an FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) scale.

Results: The study included 50 patients, after excluding 3 patients who were not eligible. The number of patients who required analgesia in the first 24 hours postoperatively was significantly lower in the quadratus lumborum block group (P < 0.05). In the quadratus lumborum block group, the postoperative 30-minute and 1-, 2-, 4-, 6-, 12-, and 24-hour FLACC scores were lower compared with those of the transversus abdominis plane block group (P < 0.05). Parent satisfaction scores were higher in the quadratus lumborum block group (P <0.05).

Conclusions: The results of this study showed that in pediatric patients undergoing unilateral inguinal hernia repair or orchiopexy the quadratus lumborum block provided longer and more effective postoperative analgesia compared with the transversus abdominis plane block.

Clinical Trials Registration: The trial was registered prospectively at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02715999).

(Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017;42: 674–679)

Truncal blocks have a place within multimodal analgesia tech niques in abdominal surgery. The application of a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block has become routine in lower and upper abdominalsurgery.1,2 In recent years, the use of ultrasoundhas led to new approaches to the TAP block.3–6

The quadratus lumborum (QL) block is a new abdominal truncal block used for somatic analgesia of both the upper and lower abdomen. AQL block allows local anesthetic to spread be tween the posterior aspect of the quadratus muscle and the medial layer of the thoracolumbar fascia, which is close to the thoracic paravertebral space.7

The QL1 block, which is applied to the anterolateral as pect of the QL muscle, was first described by Blanco8 in 2007. Later, QL block was refined and renamed as the posterior transmuscular (QL-TM) approach, referencing the Shamrock approach. The QL-TM approach injected local anesthetic into the anterior aspect of the QL muscle.9 More recently, Blanco et al 10 described a QL2 block, in which the point of injection was intentionally moved from the anterolateral side of the QL muscle to the posterior wall.

In a recent study, Blanco et al11 compared the QL2 block with the TAP block for postoperative analgesia in patients who had a cesarean delivery, concluding that the QL2 block was superior in terms of pain relief, opioid consumption, and duration of analgesia.

To our knowledge, no studies have compared a QL2 block with a classic TAP block in pediatric patients. In this randomized, double-blind, controlled study, we aimed to compare a QL and a TAP block in pediatric patients undergoing unilateral inguinal hernia repair or orchiopexy.

The study was registered prior to patient enrollment with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02715999) on March 13, 2016. The study was conducted between March 2016 and January 2017. Approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee of Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam University Medical School (no. 2016/02-05).

The study included 53 patients, aged 1 to 7 years, with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status scores of I and II. Informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents. Randomization was achieved using the closed envelope technique. All patients were candidates for unilateral inguinal hernia repair or orchiopexy under general anesthetic. Exclusion criteria included known allergies to local anesthetics, infection or redness at the injection site, anatomic anomalies or coagulation disorders, liver diseases, or unwillingness to participate in the study.

Preoperatively, all patients were premedicated with oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg. In the operation room, electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure, and peripheral oxygen saturation were monitored. If a patient had an intravenous (IV) cannula, in duction was performed using 3 mg/kg propofol. If a patient did not have an IV cannula, general anesthesia was induced with a face mask distributing 8% sevoflurane and 50% air in oxygen. Fentanyl was administered at 1 μg/kg, and a ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (Intavent-Orthofix, Maidenhead, United Kingdom) was used to secure the upper airway. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane 2% and 50% air in oxygen.

All blocks (TAP, QL) were performed by the same anesthesiologist (G.Ö.) after placement of a ProSeal laryngeal mask airway before surgery.

In both groups, the patients were placed in the lateral position, and the surgical area was cleaned with povidone iodine

FIGURE 1. Transversus abdominis plane block.

FIGURE 2. Quadratus lumborum block. White arrow shows injection point.

and high-frequency (10–18 MHz) ultrasound (MyLab Five; Esaote, Florence, Italy), using a linear probe covered with a sterile sheath (Figs. 1 and 2). In the QL block group, the probe was placed anterior and superior to the iliac crest, and the 3 abdominalwall muscles were visualized. The external abdominal oblique muscle was followed posterolaterally until the posterior border of the muscle was identified. When the probe was tilted to the attachment site of both the internal abdominal oblique muscle and the external abdominal oblique muscle over the QL,the midline of the thoracolumbar fascia was seen as a bright hyperechogenic line (Fig. 3). A 22-gauge, 80-mm Quincke-type Sono Plex needle (Pajunk, Geisingen, Germany) was inserted using an in-plane technique. The needle was directed from anterolateral to posteromedial after making a negative aspiration test with 0.5 mL normal saline to confirm the space with a hypoechoic image and hydrodissection. An injection of 0.5 mL/kg 0.2% bupivacaine was applied between the QL muscles and the thoracolumbar fascia. In the group receiving the TAP block, the probe was placed between the anterolateral abdominal wall and the iliaccrest. The external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles were identified (Fig. 4). A 22-gauge, 50-mm Quincke-type Sono Plex needle (Pajunk) was inserted using an in-plane technique. The needle was directed

FIGURE 3. Transversus abdominis plane block. White arrow shows injection point. EO indicates external oblique muscle; IO, internal oblique muscle.

from anterolateral to posteromedial toward the TAP after making a negative aspiration test with 0.5 mL normal saline toconfirmthe space with a hypoechoic image and hydrodissection. An injection of 0.5 mL/kg 0.2% bupivacaine was applied between the internal abdominal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles.

The operation began 7 to 10 minutes after the block was applied, and all patients were operated on with a standardized technique. At the end of surgery, 15 mg/kg acetaminophen IV was administered to all patients. Any complications occurring during the procedure were recorded.

Pain levels were assessed using a FLACC(Face, Legs,Activity, Cry, Consolability) scale at 30 minutes and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12,and 24 hours by the nurses and a second anesthetist blinded to group assignment in the recovery room and the surgical ward.12 When the FLACC score in the postanesthesia care unit was 4 or greater, IV tramadol 1 mg/kg was administered. Oral ibuprofen 7 mg/kg was administered to patients with a score of greater than 2 in the ward. Parents were informed about the pain evaluation, and when patients had pain at home, parents were instructed togive 7 mg/kg oral ibuprofen. The anesthesiologist recorded data received from the parents over the phone.

The primary out come was whet her there was a need for analgesia in the first 24 hours, and secondary outcomes were the time in which the first analgesia was required, FLACC scores, and parent satisfaction. Satisfaction levels of the parents were given ver bally as a level from 1 to 10, with the lowest level of satisfaction at a value of 1 and the highest level at 10.

Sample Size Estimation

The approximate sample size was calculated using the G* Power3 analysis program (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) before the study. A pilot study was con ducted on 5 patients from each group. The power analysis applied was made based on the mean number of patients who required analgesia in 24 hours, which was 0.2 (0.44) in the QL group and 0.6 (0,54) in the TAP group. The sample size was calculated at a power of 85% and a significance level of 5%, and it was de termined that it would be necessary to have approximately 24 patients per group to obtain significant statistical value.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Statistics for Macintosh program, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean and SD, and as the number of cases (n) and the corresponding percent age (%) for nominal variables. T tests were performed for nor mally continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric variables.

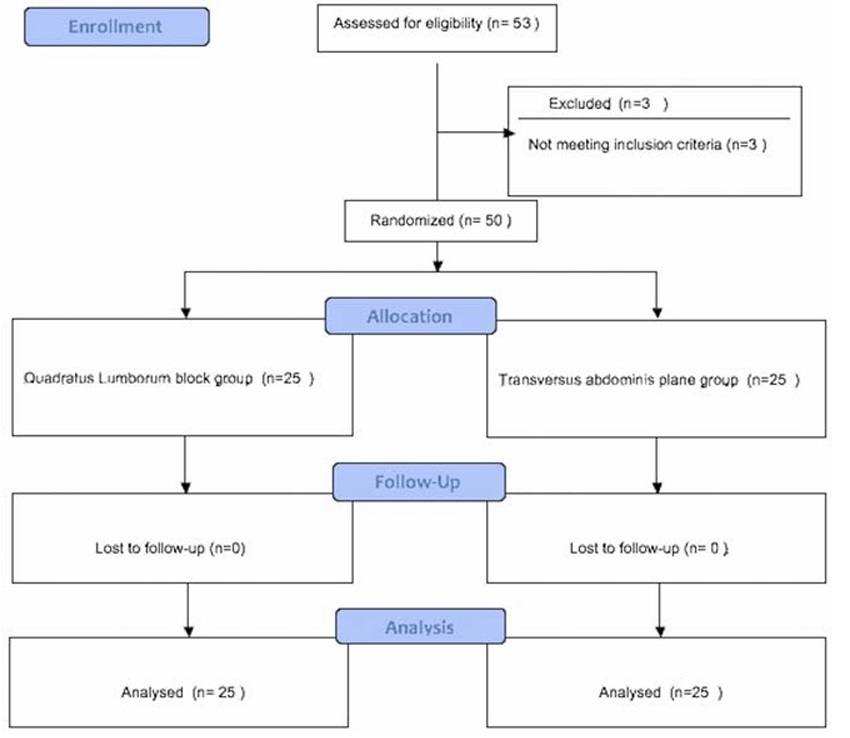

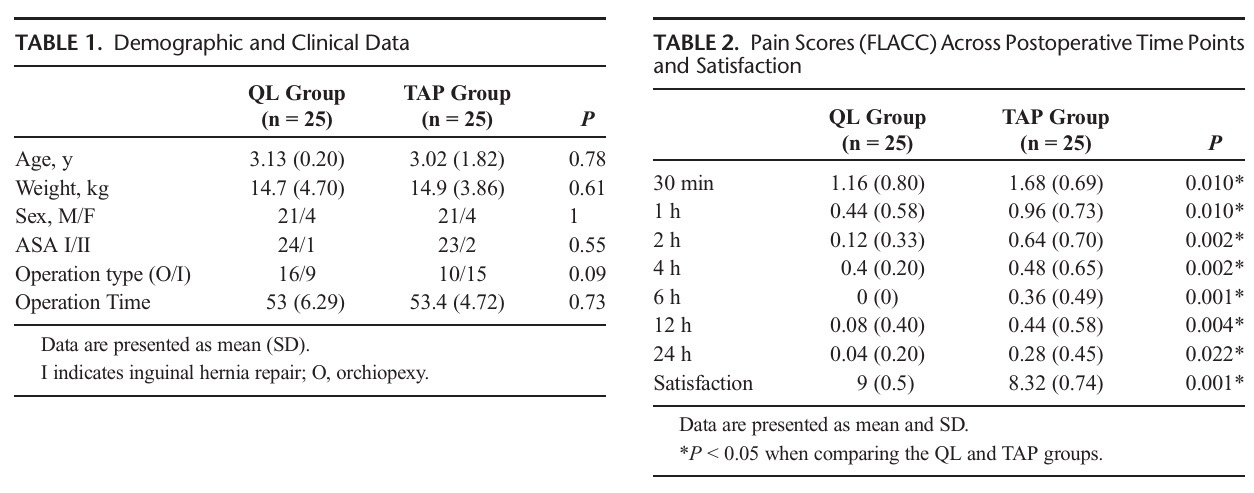

The study included 53 patients, after excluding 3 patients who were not eligible (Fig. 5). No significant differences were observed between the groups based on age, sex, weight, ASA score, operation type, or operating time (Table 1).

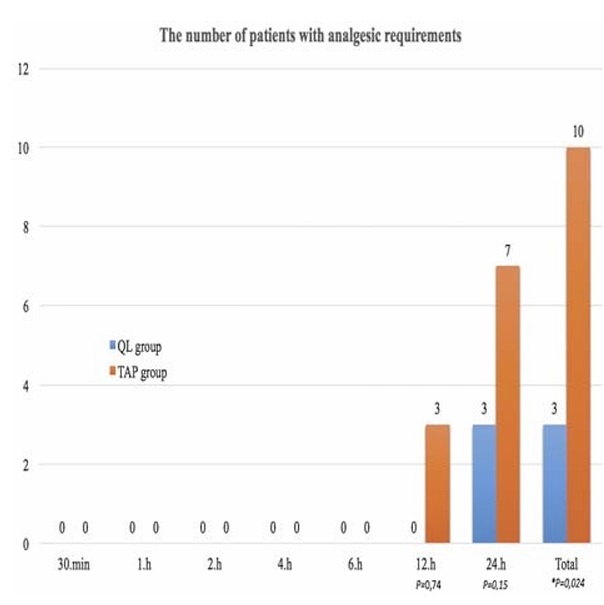

The number of patients who required analgesia in the first 24 hours, postoperatively, was significantly lower in the QL block group than in the TAP block group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6).

In the QL block group, the postoperative 30-minute and 1-, 2-, 4-, 6-, 12-, and 24-hour FLACC scores were lower compared with those of the TAP block group (P < 0.05; Table 2). Parent satisfaction scores were higher in the QL block group comparedwith the TAP block group (P < 0.05; Table 2).

There were no post operative complications, such as hypotension, arrhythmia, bradycardia, deterioration in vital signs, nausea, or vomiting observed in any of the patients.

FIGURE 5. CONSORT flowchart.

The time in which patients required the first analgesia was determined to be 15 hours in the QL block group and 10 hours in the TAP group.

To our knowledge,this is the first double-blind,randomized, prospective study comparing the QL and TAP blocks for postoperative pain relief after lower abdominal surgery in children.

The results of the study showed that the QL block provided more effective pain relief compared with the TAP block and did not have any adverse effects.In lower abdominal surgery in children, such as hernia repair and or chiopexy, various techniques used have included the TAP block; caudal block, ilioinguinal block performed by the anesthesiologist;and wound in filtration, performedbythesurgeon.13–15

The QL block is a newly defined procedure,which can be applied in lower and upper abdominal surgery. Blanco et al 8,10 defined the QL1 block with an anterolateral approach in abdominoplasty operations.In magnetic resonance imaging studies, Blanco et al 8,10 suggested that the QL 2 block, positioned between the posterior

edge of the QL and the thoracolumbar fascia,could be used more

FIGURE 6. The time distribution of rescue analgesia.

effectively and safely with along-lasting effect of anesthesia to the paravertebral area.

In a recent study, Blanco et al 11 compared the efficacy of the TAP and QL blocks for postoperative analgesia in cesarean delivery operations. It was reported that the QL block was superior to the TAP block with respect to the duration of the effect, pain relief, opioid consumption,andthesuccessoftheblock.11Inthecurrent study, the QL block was observed to be statistically significantly superior tothe TAP block when comparisons were made based on the number of patients requiring analgesia in the first 24 hours; the FLACC scores at 30 minute sand at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 hours; and parent satisfaction.The QL block was determined to have a longer duration of effectiveness.These results were seen to be consistent with those of Blancoetal.11

The TAP block is a procedure that is frequently used for postoperative analgesia in pediatric upper and lower abdominal operations. The reliability and ease of use under ultrasound guidance have increased its popularity.13 Murouchi et al 16 examined the relationship between the efficacy of the TAP and QL 2 blocks and local anesthetics blood levels in adults and reported that the patients’ local anesthetic blood levels were higher when given the TAP block than when the QL 2 block was used; however, the QL 2 block was more effective. As with Blanco’s results, this was associated with the paravertebral spread.11,16 As the local anesthetic level in the blood was lower in the QL 2 block compared with the TAP block, the QL 2 block may be more reliable; this could be a reason for selecting the QLb lock for children.In addition,the surface formation of the QL 2 block can be applied in both a supine and a lateral position,and it can be easily applied with a linear probe in children,which could increase its use in multimodal an algesia in patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

In the comparison of the efficacy of TAP block with that of QL block in abdominal surgery, there are the ories about the QL block mechanism related to the extent of paravertebral local an aesthetic area.There are also previous studies that have reported

the possibility of the L1 anterior branch not obtaining anesthesia in the application of classic (lateral) TAP block and others confirming L1 involvement in dual TAP block application.17,18

There is little information in the literature explaining the use of a QL block for postoperative analgesia in children. Visoiu and Yakovleva 19 were the first to report that analgesia was provided with a catheter using a QL block in a lateral position in pediatric

colostomy repair. Chakraborty et al 20 applied continuous QL block with a catheter after a nephrectomy for Wilms tumor in pediatric patients while in a supine position, and they also reported that successful postoperative analgesia was obtained.

In pyeloplasty performed on 5 children in the lateral position, Baidya et al21 used a QL-TM block with the application of a single-dose injection transmuscularly, between the psoas major and the QL, and it was reported that postoperative analgesia was successful. Murouchi22 described the intramuscular approach in a pediatric patient undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy and re ported successful analgesia with the bilateral application of a QL-IM block. However, none of the studies mentioned the use of a QL block in open lower abdominal surgery in pediatric patients, and there have been no comparisons of the QL block and TAP block in pediatric cases.

In the current study, the QL block was applied with the patient in a lateral position, with an anterior approach, to the posterior edge of the QL muscle. An interfascial triangle was formed by the local anesthesia at the point where the fascia of the external abdominal oblique muscle and the internal abdominal oblique muscle join, between the latissimus dorsi and the QL muscle, and where there was hyperechogenicity of the midlayer of the thoracolumbar fascia attached over the QL muscle. Blanco et al11 applied this block in the supine position with a QL2 approach.

Although the mechanism of the QL block has not been fully clarified, cadaveric studies have been conducted to examine the spread of local anesthesia. Carline et al23 applied blocks to 10 cadavers with the QL1, QL2, and QL-TM approaches. Although in

different fascial planes, the local anesthetic in the QL1 (between the deep and midlayer of the thoracolumbar fascia) and QL2 blocks (between the superficial and midlayer of the thoracolumbar fascia, more toward the posterior) had spread similarly to the

subcostal nerves, but there was no evidence of spread to the paravertebral area. In the transmuscular approach, it was reported that the lumbar L1–L3 nerve roots were more affected, and no spread to the thoracic dermatome was observed.23

In addition to the area of spread of the local anesthetic not being fully understood in the QL block, complications may be encountered such as hypotension and muscle weakness, which can be seen in paravertebral and lumbar plexus blocks. It was reported that in a case undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery

unilateral weakness was experienced in hip flexion and knee extension, which lasted for approximately 18 hours after the application of the QL block. However, this seems to be the only reported complication in literature.24 Blanco et al11 reported that no complications were encountered in patients who had a cesarean delivery, particularly because the QL2 block is a superficial and safe block.

In the current study, no complications developed in either group. However, there was not adequate power to show a difference in uncommon complications. No opioids were required, and patients could be discharged early; the surgical team viewed these as positive aspects.

Measurements could not be taken of the sensory block level of the QL and TAP block sapplied to the children aged 1 to 7 years, which could be a limitation of the study. We do not know if a higher level of dermatomal sensory block was provided compared with the TAP block. In the first postoperative 24 hours, the total analgesia use was determined to be a single dose of 7 mg/kg ibuprofen at the earliest time of the 15th hour in 3 patients in the QL block group. In the TAP block group, the earliest single dose of 7 mg/kg ibuprofen was given at the 10th hour in 10 patients. After discharge, some patients were given analgesia at home, and this can be attributed to the child becoming more active and subsequently experiencing pain.

There is a need for much further research in this area with comparisons of the QL,TAP block, and wound infiltration groups in abdominal surgeries for pediatric patients and for adults.

The results of this study showed that in pediatric patients undergoing unilateral inguinal hernia or orchiopexy the QL block provided longer and more effective postoperative analgesia compared with the TAP block, which has been inuse for many years.

1. Abdallah FW, Chan VW, Brull R. Transversus abdominis plane block: a

systematic review. RegAnesthPainMed. 2012;37:193–209.

2. De Oliveira GS Jr, Castro-Alves LJ, Nader A, Kendall MC,

McCarthy RJ. Transversus abdominis plane block to ameliorate

postoperative pain outcomes after laparoscopic surgery: a

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:

454–463.

3. Hebbard P, Fujiwara Y, Shibata Y, Royse C. Ultrasound-guided

transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Anaesth Intensive Care.

2007;35:616–617.

4. Tran TM, Ivanusic JJ, Hebbard P, Barrington MJ. Determination of spread

of injectate after ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: a

cadaveric study. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:123–127.

5. Walter EJ, Smith P, Albertyn R, Uncles DR. Ultrasound imaging for

transversus abdominis blocks. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:211.

6. Hebbard P. Subcostal transversus abdominis plane block under ultrasound

guidance. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:674–675.

7. Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The

thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations.

JAnat. 2012;221:507–536.

8. Blanco R. Tap block under ultrasound guidance: the description of a

“no pops” technique 271 [abstract]. RegAnesthPainMed. 2007;

32:S130.

9. DamM,HansenCK,BørglumJ,ChanV,BendtsenTF.Atransverse

oblique approach to the transmuscular quadratus lumborum block.

Anaesthesia. 2016;71:603–604.

10. BlancoR,Ansari T, Girgis E.Quadratus lumborumblock for postoperative

pain after caesarean section: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J

Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:812–818.

11. Blanco R, Ansari T, Riad W, Shetty N. Quadratus lumborum block versus

transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain after cesarean

delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med.2016;41:

757–762.

12. Manworren RC, Hynan LS. Clinical validation of FLACC: preverbal

patient pain scale. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29:140–146.

13. Kendigelen P, Tutuncu AC, Erbabacan E, et al. Ultrasound-assisted

transversus abdominis plane block vs wound infiltration in pediatric

patient with inguinal hernia: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth.

2016;30:9–14.

14. Sethi N,PantD,DuttaA,KoulA,SoodJ,ChughPT.Comparisonofcaudal

epidural block and ultrasonography-guided transversus abdominis plane

blockfor painrelief inchildren undergoing lowerabdominal surgery. JClin

Anesth. 2016;33:322–329.

15. FredricksonMJ,PaineC,HamillJ.Improvedanalgesiawiththeilioinguinal

block compared to the transversus abdominis plane block after pediatric

inguinal surgery: a prospective randomized trial. Paediatr Anaesth.2010;

20:1022–1027.

16. Murouchi T, Iwasaki S, Yamakage M. Quadratus lumborum block:

analgesic effects and chronological ropivacaine concentrations

after laparoscopic surgery. RegAnesthPainMed. 2016;41:

146–150.

17. Borglum J, Gögenur İ, Bendtsen T. Abdominal wall blocks in adults. Curr

Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016;29:638–643.

18. SondekoppamRV,BrookesJ,MorrisL,Johnson M,GanapathyS.Injectate

spread following ultrasound-guided lateral to medial approach for dual

transversus abdominis plane blocks. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand.2015;59:

369–376.

19. Visoiu M, Yakovleva N. Continuous postoperative analgesia via

quadratus lumborum block—an alternative to transversus

abdominis plane block. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:

959–961.

20. Chakraborty A, Goswami J, Patro V. Ultrasound-guided continuous

quadratus lumborum block for postoperative analgesia in a pediatric

patient. A A Case Rep. 2015;4:34–36.

21. Baidya DK, Maitra S,Arora MK, AgarwalA.Quadratus lumborum block:

an effective method of perioperative analgesia in children undergoing

pyeloplasty. JClinAnesth. 2015;27:694–696.

22. Murouchi T. Quadratus lumborum block intramuscular approach

for pediatric surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2016;2016:135–136.

23. Carline L,McLeodGA,LambC.Acadaverstudycomparingspreadofdye

and nerve involvement after three different quadratus lumborum blocks.

Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:387–394.

24. Wikner M. Unexpected motor weakness following quadratus lumborum

block for gynaecological laparoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:230–232.